One of the perks of taking an extended hiatus is having actually new developments to talk about upon returning —

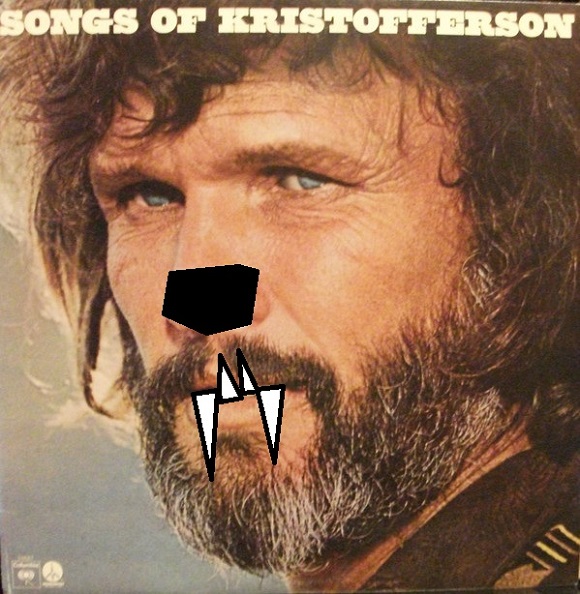

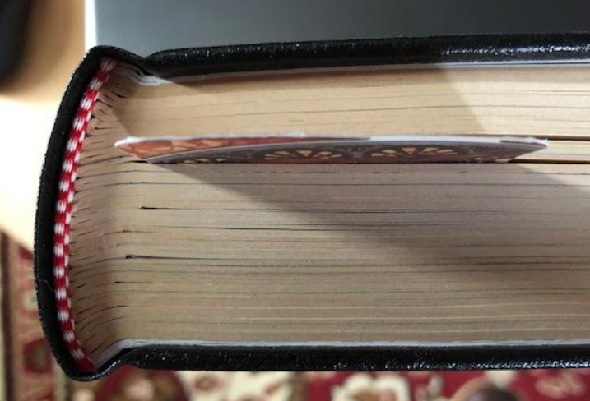

— things such as the above object of beauty.

The collection is not a hoax or imaginary story. Nor, I regret to inform you, is it the product of DC’s trade collections department coming to their senses. It is a one-of-a-kind custom jobber I undertook on my own (with the help of a bookbinding firm, of course).

The matter of beloved “never-have-or-will-ever-be-collected” runs and series has been at the back of my mind since I started consolidating the perennial (and sentimental) favorites from two dozen longboxes into a smaller and more manageable set of trade paperback and hardcover editions. The vast majority of these “essentials” were available in some collected form or another, though there were a handful of top-tier cherished runs which — for licensing or legal or economic reasons — never made the trade grade.

Most of these strays were DC offerings from the immediate pre-and-post-Crisis periods, a motley assortment of faded flashes in the pan or decently entertaining efforts which never gained traction with fans. At the top of the list was Atari Force, “a great series doomed by a troubled license” (as the owner of my local comic shop put it back in the day).

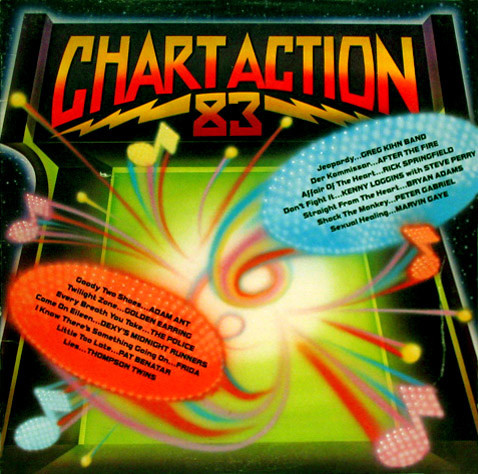

The twenty issue series (followed by a one-off “special” of inventoried back-up material) followed up on the events of the digest-sized comics packed in with certain Atari 2600 games in a bit of intra-divisional marketing synergy. (Both DC and Atari were owned by the Warner Brothers media empire at the time.) Connections between the comics and the games were tenuous at best outside of a few referential names and nods to Star Raiders lore.

The pack-in digests weren’t bad, but hewed closely to the generic pre-Star Wars 70s sci-fi template. A multi-ethnic bunch of experts were tapped by the Atari Institute to traverse the multiverse in the dimension-hopping Scanner One spaceship in hopes of finding a “New Earth” for humanity before the old Earth became uninhabitable. Oh, and they argued and fell in love with each other while kicking evil alien monstrosity ass.

The monthly series used that as springboard for jumping a ahead a couple of decades, where New Earth is thriving and the super-powered kids of the original crew, along with various hangers-on and associates, get recruited by the middle-aged embittered leader of the previous mission to determine if the evil alien monstrosity somehow managed to survive its ass-kicking.

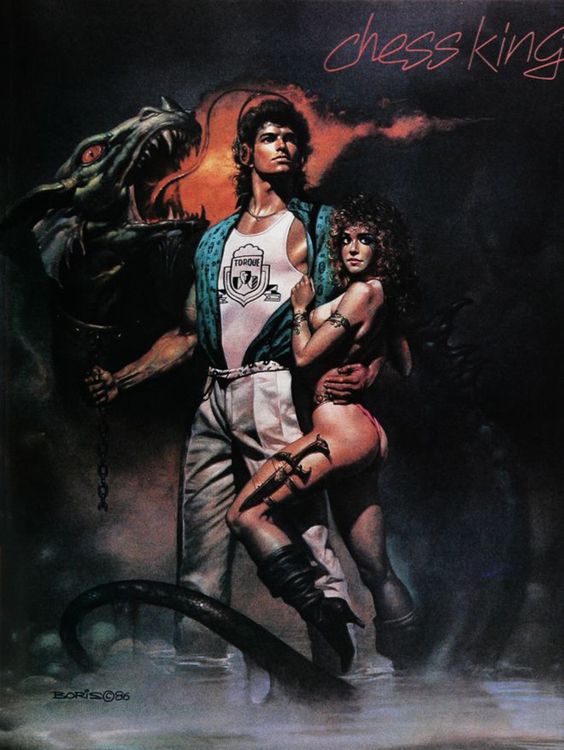

That’s the short version — because I don’t feel like writing up a long version — but the vibe of the regular series fell somewhere in-between Star Wars and Legion of Super-Heroes. It code switches between space opera and super-team in way that played to the strengths of the medium, instead of crashing up against it as most Big Two sci-fi comics series did in ’70s and ’80s. Think of it as DC’s answer to Marvel’s Micronauts, but with a clearer through line.

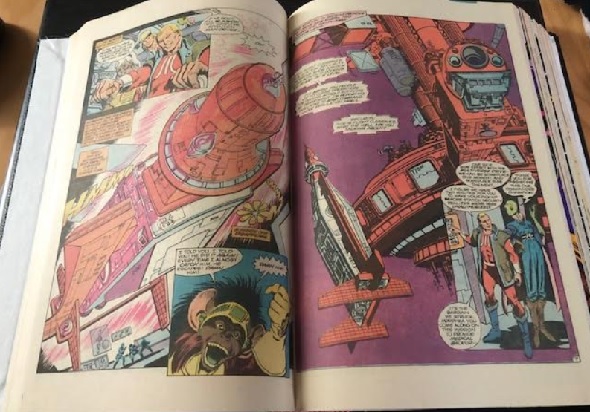

It helped that the first half of the run was (mostly) illustrated by José Luis GarcÃa-López, who got s chance to cut loose with all manner of groovy character designs and futuristic tech, but everyone involved brought their best to the project. Ricardo Villagrán’s finishes meshed beautifully with GarcÃa-López’s pencilwork, Gerry Conway turned out some of the sharpest writing he’d do that decade, Tom Zukio did some fantastic coloring-for-effect work, and Bob Lappan pulled out the stops when it came to lettering alien speech that slyly conveyed the general gist of the dialogue.

Even after GarcÃa-López and Conway tapped out halfway through the series, the new team of Eduardo Barreto and Mike Baron still kept things chugging along nicely through the home stretch.

Atari Force was one on my favorite series during my tweener years. It wasn’t due to the videogame connection, but because it was a really solid team book with an interesting cast of characters overseen by an excellent creative team (or teams, technically). It was an especially impressive feat considering that I had yet to outgrow my “if it ain’t in Big Two continuity, I’m not interested” biases at the time I picked up my first issue of the series.

I was sad to see it end, though it took a few years before I realized that the “we always planned it as a 20-issue run” excuse given at the time for calling it a day was bullshit masking Warners’ desire to shed themselves of the cash-sink Atari had turned into after the domestic videogame market crashed. Never a hot property in speculative circles, the back issues became quarter-bin staples for the following couple of decades (which is how I ended up completing my run and replacing my beat-to-shit original issues).

It’s a series I enjoy revisiting every couple of years, a rare case where nostalgia is a value added thing and not some sweet coating on a bitter-in-hindsight pill. Most of the trades on my bookshelf don’t attain that state of grace, which is why I really wanted an Atari Force collection — even if I had to see to it myself.

I knew professional and DIY binding was a thing from some old Newsarama and Comics Alliance posts, but wasn’t clear on the specifics or price or other details. The notion of binding up Atari Force and other uncollected runs went into the same mental space as the rest my vague aspirational projects — the “I will look into it later” file.

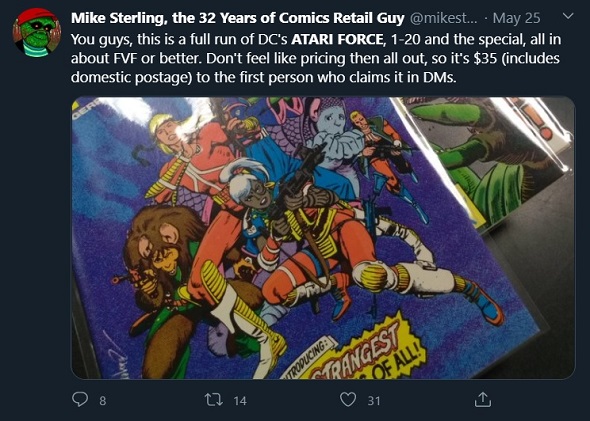

It likely would have stayed there until the heat death of the universe if long time pal and comics retailer extraordinaire Mike Sterling hadn’t lobbed this into his Twitter feed a few months ago.

A complete Atari Force run in clean condition from a retailer I trust and for a decent price? I’m not one for omens, but this was too on-the-nose to pass up. Plus, it was a chance to toss a little dough at a small business at a moment when the pandemic had screwed with their bottom line. Direct messages were sent, money was exchanged, and soon I had a pile of ready to bind comics on my “to-do” shelf.

…where they sat for another month before I finally knuckled down and did the research about getting the job done. Between the bindery’s detailed FAQ page and a blog post from a person who put up screenshots of an order form they’d submitted with further clarifications, I managed to get the stack prepped and shipped out for processing. About seven weeks later, I got an invoice from the bindery, promptly paid it, and had the finished product in my hands a week later.

I’m not going to lie. I held the tome to my chest several times in the first couple of days after it arrived and whispered “I love you” to it (when Maura and the Kid were out of earshot, of course). I even cleared it a place of honor on the Very Important Books part of my shelf, alongside Retro Hell, the OHOTMU Omnibus and the 1980 and 1981 Sears Wish Books.

To answer some questions I was asked elsewhere about the process:

The bindery I used was Herring and Robinson. The only extras I selected were headbands (the cloth bits at the top and bottom of the spine) and the small “DC Bullet” diestamp above the title. The total including shipping came out to $40.

Yes, there’s a sliver of loss close to the spine edge of the page. It’s not a lot (though your metrics for that may differ from mine) and some of it depends on how the original pages were centered in the component comics and the overall thickness of the bound edition. I really haven’t tried to see how wide I could open the book because it is my precious darling and I won’t do anything that might hurt it.

I got exactly what I had been hoping for — a handsome and handy collection of a comics series that can be shelved in my living room and not relegated to some difficult to access attic longbox. I’m happy enough with the work that I’ve already sent off another pair of runs — the complete Young Heroes in Love and the first eighteen issues (and first annual) of the 80s Captain Atom series — for similar treatment.

I probably won’t hug those, though.